It would be easy to think that someone can simply buy a drone and start flying it around, but drone regulation has changed dramatically. Today, we have reached new levels with risk categorization, airworthiness, and remote identification guidelines. But let’s start at the beginning…

The 2021 Drone Regulation – What is new? What is planned?

Pioneering the Early Days

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) – the “mother” of global aviation standards – started exploring drone technology in 2005 with the goal of assessing activities and use of standards for drones in the civil airspace. The results were summarized in the ICAO Circular “Unmanned Aircraft Systems” in 2011 and national aviation authorities adopted these efforts. France (2015) was one of the first countries to set the basic framework for the nowadays common drone regulation rules, e.g. to operate below 400-500 feet or to keep the drone within visual line of sight. Other countries followed slowly but steadily.

So did the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). These are the leading aviation legislators whose legislative system and standards have been adapted in many other countries.

In June 2016, the publication of FAA Part 107 changed the regulatory framework dramatically. This legislation allowed drone users an easier access to the market. The challenge: Everyone was now able to fly drones under Part107 so that the commercial market grew strongly through easy controllable small drones which offered the possibility to apply new use cases. The effect was that the access to the airspace was very simple and it got very hard to manage and enforce the 107 rules. Airspace violations grew and neglect of rules increased.

Part 107 was designed for “easy” or non-complex applications. Everything else and more complex was nearly impossible given that waivers were not granted in the majority of cases. There was no standardized way to handle waivers, so they were checked individually in an event-based manner. This caused long lead times due to the administrative bottleneck and due to the lack of learnings/references to a high rejection rate. Typical requests were BVLOS missions, operation over people and flights at night.

The European Way

EASA at this point was not inactive; it closely observed the developments in the USA. All nations within in the EU had individual (more or less permissive) regulatory frameworks at that time. The EASA took these learnings into consideration. This explains the huge time gap for when they published their final drone operation Regulation (EU) 2019/947… exactly 3 years later in June 2019.

Some of the key differences include how to make risk assessments and how to apply for approval. Predefined risk categories are also included and make this framework much easier to handle in comparison with FAA.

The year 2021 is very important in this regard, because the new rules for operating drones have come into effect for users in the EASA member states since December 31, 2020.

Recently, the FAA also considered a predefined risk categorization for the first time with the publication of the new rule “The Operation of Unmanned Aircraft Systems Over People” (OOP) on December 28th, 2020. This rule is very similar to the risk categorization of the specific category of (EU) 2019/947, because it enables a clear identification of low, medium and high-risk operation and gives direction of what is needed to be in compliance.

These predefined risk categories of the EASA and FAA mean a strong simplification for the end user and are not only accessible in the US or EASA member states. Other countries like Singapore or Australia, have also published similar rules. You can find more info about each country’s regulatory framework in our Drone Regulation Report 2020.

To Summarize what is possible now: operating simple low-risk flights without any license is standard throughout Europe today.

New Requirements to Maximize Potential

Commercial aviation is strongly regulated and since drones and aircrafts will share the same airspace, drone technology needs to be integrated into these aviation frameworks. In other words, the (drone) rules that are needed to use the drones’ full potential today are still missing. The risk-oriented approach in the EU and USA (as well as many other countries), is ideally suited for defining new, more advanced and complex missions in this airspace. To do this, operational, airworthiness and personnel standards are required. There are some standards available (e.g. JARUS SORA) but we need more, especially in the field of airworthiness. Airworthiness means the measure of a drone’s suitability for safe flight, which is an essential part of drone certification.

To make BVLOS and OOP possible, both aviation authorities are currently working hard on airworthiness standards, but also on remote identification rules to enable the integration of drones into the airspace.

In this field, the initial steps were done by the FAA and EASA at the end of 2020. The EASA published their “special conditions” for the issuance of a type certificate for drones up to 600kg to be in compliance with drone operation under medium risk in the “specific category” of (EU) 2019/947. The FAA showed a different approach by publishing airworthiness criteria of 10 different drone types with max weight of 40kg (89pounds) – e.g. Wingcopter model 198, Zipline model Sparrow or Percepto model 2.4.

The new remote ID rule of the FAA requires modifying drone hardware to enable the permanent broadcast of identification and location of the drone and control station. When the drone is intended to be operated in the US airspace this means that every drone manufacturer needs to add a Remote ID Broadcast Module within 18 months after the rule`s effective date (which was December 28th, 2020). It’s worth mentioning here that ADS-B transponders are not allowed as broadcast devices to make a clear distinction from manned air traffic.

The terms “airworthiness” and “remote ID” are not relevant for end users – however, it is a challenging task for manufacturers to comply with these new requirements. As mentioned above, these requirements are only applicable for complex missions – all other, less complex types of mission do not have to comply with these requirements.

Are these standards sufficient to create a certain level of safety? Aviation experts say that drone regulation and standards need to be supplemented with safety culture. A management system has a human-centered focus and involves all stakeholders who participate to operate drones. Such a system is called Safety Management System (SMS), which puts a focus on procedures (e.g. training, occurrence reporting), as well as on safety and error management culture. An initial guide for the drone industry has already been published by the National Business Aviation Association. The implementation of such a management system can be simple or very complex – depending on the size and nature of the company. SMS will play an important role in drone operation. The EASA has already integrated the SMS into the (EU) 2019/947 rule as a prerequisite for the approval of a Light Unmanned Certificate (LUC).

The next two years

In the next two years operators and manufacturers face the challenge of complying with new requirements (rules and standards) to fly advanced missions. This may sound bad but is actually good news since it finally allows them to use drones to their fullest potential. Operation over people, at night, beyond visual line of sight or a combination of these three will leverage the disruptive potential of drone technology and dramatically push the market forward.

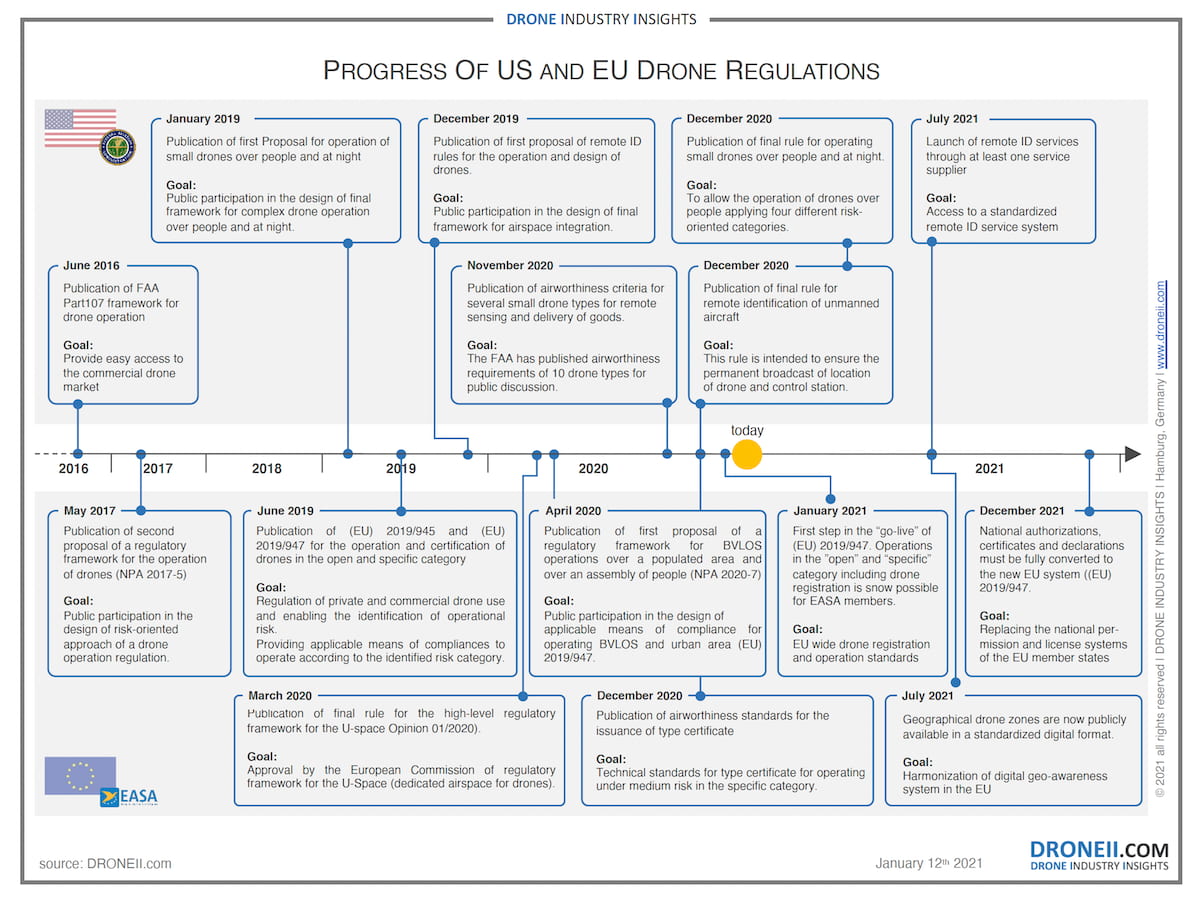

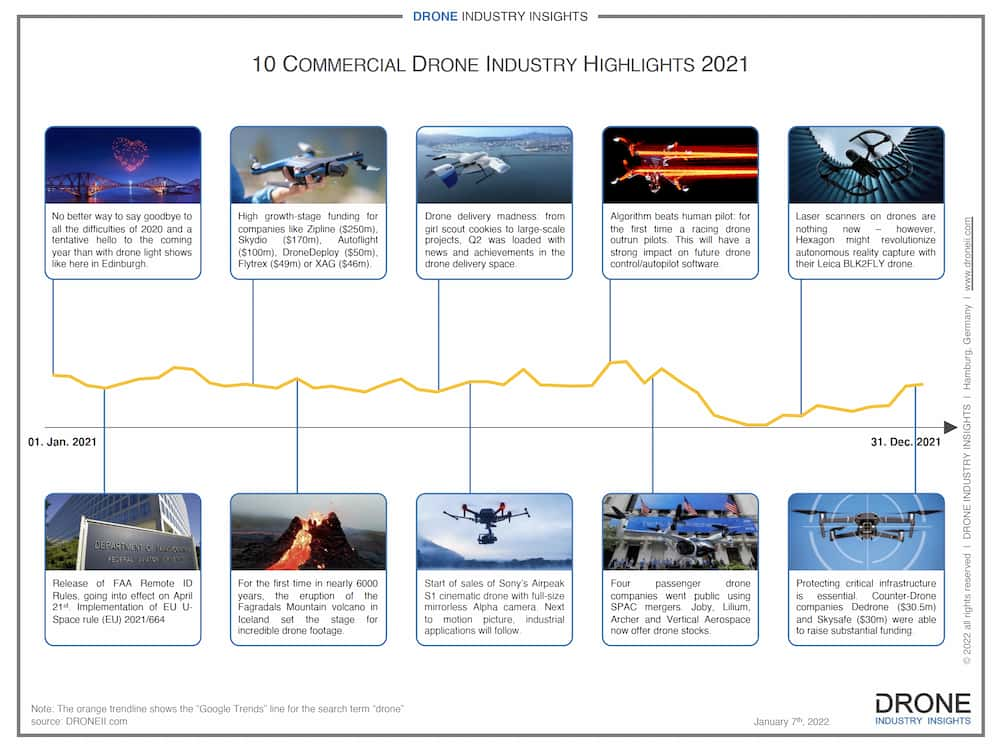

Download our FREE Infographic: Progress of the USA and EU Drone Regulation

This infographic, “Progress of the USA and EU Drone Regulation“, shows a selection of regulatory milestones from the past years as well future changes.

Besides his financial oversight, Hendrik is an expert in aviation law and UAV regulation with more than 10 years of experience. Not only does he consult on all regulation questions, but Hendrik also writes the yearly drone investments report. Prior to launching DRONEII, at Lufthansa Technik he was the single point of contact to Civil Aviation Authorities (CAA) of Germany, Middle East and Asia.